Carnatic classical music, a centuries-old tradition, stands as a prominent and deeply revered form of classical music in South India. Its roots trace back to ancient times, and it has evolved into a complex and sophisticated musical form that is rich in tradition and cultural significance. This article explores the history, theory, and practice of Carnatic classical music, offering insights into its unique characteristics and enduring appeal.

I. Origins and Historical Development

1. Ancient Beginnings

Carnatic music’s origins can be traced back to the Vedic period (1500-500 BCE). The Vedas, ancient Indian scriptures, contain hymns and chants that form the earliest examples of Indian music. These chants, known as “Sama Veda,” were sung in a specific melodic format, laying the foundation for Indian classical music.

2. The Sangam Period

During the Sangam period (300 BCE – 300 CE), Tamil literature flourished, and music played a significant role in Tamil culture. The poems and songs of this era provide insights into the early forms of Carnatic music. The compositions were often performed in temples and royal courts, reflecting the close connection between music, religion, and society.

3. The Bhakti Movement

The Bhakti movement (7th to 18th centuries) was a major driving force in the development of Carnatic music. Devotional poets like the Alvars and Nayanars composed hymns in praise of Hindu deities. These compositions, known as “bhajans” and “kritis,” became central to Carnatic music. The movement emphasized personal devotion and emotional expression, which are still key aspects of Carnatic performances today.

4. The Trinity of Carnatic Music

The 18th century saw the emergence of the “Trinity of Carnatic Music” – Tyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar, and Syama Sastri. These composers are revered for their contributions to the Carnatic repertoire. Their compositions, characterized by intricate melodies and profound lyrics, continue to be performed and studied by musicians worldwide.

II. Theoretical Foundations

1. Raga and Tala

At the heart of Carnatic music are the concepts of raga and tala. A raga is a melodic framework consisting of a specific set of notes, with rules for their progression. It evokes particular emotions and moods, making each raga unique. There are hundreds of ragas, each with its distinct identity and expressive power.

Tala, on the other hand, refers to the rhythmic aspect of Carnatic music. It is a cycle of beats that provides the temporal structure for a composition. There are several talas, each with a specific pattern of beats and subdivisions. The interplay between raga and tala forms the essence of Carnatic music.

2. Sruti and Laya

Sruti, or pitch, is another fundamental concept. It refers to the precise tuning of notes and is often compared to the drone in Western music. The tambura, a stringed instrument, is typically used to provide a continuous drone, helping the musician maintain the correct pitch.

Laya, or tempo, is the speed at which a composition is performed. Carnatic music allows for a wide range of tempos, from slow and meditative to fast and energetic. The musician’s control over laya is crucial in delivering a captivating performance.

3. Compositional Forms

Carnatic music features various compositional forms, each with its structure and purpose. Some of the most prominent forms include:

Varnam: A foundational form used for practice and performance, showcasing the raga’s essential features.

Kriti: A devotional composition with lyrics in praise of deities, often featuring a pallavi (refrain), anupallavi (secondary theme), and charanam (concluding section).

Alapana: An improvisational form where the musician explores the raga’s nuances without rhythmic accompaniment.

Kalpana Swara: Improvised solfege, where the musician creates spontaneous melodic phrases within the raga’s framework.

Thillana: A rhythmic and lively composition, usually performed at the end of a concert.

III. Instruments of Carnatic Music

1. The Veena

The veena is one of the oldest and most revered instruments in Carnatic music. It is a plucked string instrument with a rich, resonant sound. The veena has a long neck with frets and a large resonating body. It is capable of producing intricate melodies and is often used in solo performances as well as accompaniment.

2. The Mridangam

The mridangam is a double-headed drum that serves as the primary rhythmic accompaniment in Carnatic music. It is made of wood and has two drumheads of different sizes, allowing for a wide range of tones. The mridangam player provides the rhythmic framework and enhances the dynamic interplay between the musician and the percussionist.

3. The Violin

The violin, introduced to Carnatic music in the 19th century, has become an integral part of the tradition. It is played in a seated position, with the instrument resting on the ankle. The violin’s versatility and expressive capabilities make it a popular choice for both solo and accompaniment performances.

4. The Flute

The bamboo flute, known as the venu, is a traditional wind instrument used in Carnatic music. It produces a mellow and soulful sound. The venu is played by blowing air into a hole and covering and uncovering finger holes to produce different notes. It is commonly used in both solo and ensemble settings.

5. The Tambura

The tambura is a stringed instrument that provides the drone in Carnatic music. It has four strings, tuned to specific pitches, and is plucked continuously throughout a performance. The tambura’s steady drone helps the musician maintain the correct pitch and creates a harmonic backdrop for the melody.

IV. Learning and Performing Carnatic Music

1. Guru-Shishya Tradition

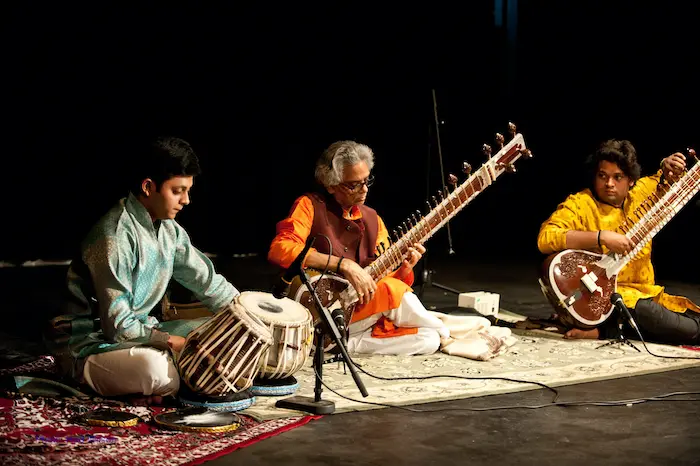

The traditional method of learning Carnatic music is through the guru-shishya (teacher-student) tradition. This system emphasizes close and personal instruction from a guru to a shishya. The student learns by observing, imitating, and internalizing the guru’s teachings. This method ensures the transmission of musical knowledge and nuances from one generation to the next.

2. Practice and Discipline

Mastering Carnatic music requires rigorous practice and discipline. Students spend years honing their skills, starting with basic exercises and gradually progressing to more complex compositions. Regular practice of varnam, kritis, and improvisation is essential for developing technical proficiency and artistic expression.

3. Concert Performance

A typical Carnatic concert, known as a kutcheri, is a structured yet flexible presentation of music. It usually begins with a varnam, followed by a series of kritis in different ragas and talas. The concert may include an alapana (raga exploration), kalpana swaras (improvised solfege), and a main item featuring a detailed exploration of a major raga and tala. The performance concludes with lighter pieces, such as thillana and bhajans.

4. Role of Accompanists

Accompanists play a crucial role in Carnatic concerts. The mridangam provides rhythmic support, while instruments like the violin and flute offer melodic accompaniment. The interaction between the main artist and the accompanists adds depth and complexity to the performance, creating a rich and immersive musical experience.

V. Contemporary Trends and Innovations

1. Fusion and Collaboration

In recent years, Carnatic music has seen an increasing trend of fusion and collaboration with other musical genres. Artists experiment with blending Carnatic elements with Western classical, jazz, and world music, creating new and exciting sounds. These collaborations have broadened the audience for Carnatic music and introduced it to a global stage.

2. Digital Platforms

The advent of digital technology has revolutionized the dissemination and consumption of Carnatic music. Online platforms, such as YouTube, streaming services, and social media, allow musicians to reach a wider audience. Virtual concerts and online tutorials have made learning and experiencing Carnatic music more accessible than ever before.

3. Preservation of Tradition

Despite these innovations, there is a strong emphasis on preserving the traditional aspects of Carnatic music. Organizations and institutions dedicated to Carnatic music work tirelessly to document and archive compositions, promote classical performances, and support the training of young musicians. Festivals and conferences provide platforms for artists to showcase their talent and share their knowledge.

VI. Cultural Significance and Global Impact

1. Spiritual and Emotional Connection

Carnatic music is deeply intertwined with spirituality and emotional expression. The devotional nature of the compositions, the emphasis on bhakti (devotion), and the ability to convey complex emotions through music make Carnatic performances a profound experience for both the musician and the listener.

2. International Recognition

Carnatic music has gained international recognition and admiration. Musicians from South India have performed on prestigious stages worldwide, earning acclaim for their virtuosity and creativity. The global audience’s appreciation for Carnatic music underscores its universal appeal and timeless relevance.

3. Educational Outreach

Educational institutions and music academies around the world offer courses and workshops in Carnatic music. These programs attract students from diverse backgrounds, fostering cross-cultural understanding and appreciation. The study of Carnatic music provides valuable insights into Indian culture, history, and artistic traditions.

See Also: 6 Classical Music Pieces Inspired by Swans: All You Want to Know

VII. Conclusion

Carnatic classical music is a rich and multifaceted tradition that has stood the test of time. Its intricate theoretical foundations, diverse compositional forms, and expressive potential make it a unique and captivating art form. The dedication of musicians, the support of institutions, and the enthusiasm of audiences ensure that Carnatic music will continue to thrive and inspire for generations to come. Whether experienced in a traditional kutcheri or through a modern digital platform, Carnatic music offers a deep and transformative connection to the cultural heritage of South India.